I‘ve always been fond of learning things that have little long-term application.

So when I followed my English-teaching girlfriend to Thailand for five months earlier this year, I jumped at the opportunity to (try and) learn the Thai language.

What follows is a case study I hope other language enthusiasts/pursuers of randomness can use when considering Thai as their next target language. In it, I detail my learning strategy (or lack thereof), quirks and challenges, and my “results” that I hope can all give a feel for what studying this tongue in its motherland is like.

—

The Thai language has two reputations:

- it’s impossible for Westerners to learn;

- wanting to learn it means you’re interested in ‘negotiating’ with certain ‘individuals’ about ‘acts’ that may or may not involve ping-pong balls.

The stigma surrounding its difficulty is more or less backed up by the Foreign Service Institute’s ranking of how many supposed classroom hours it takes for a native English speaker to reach proficiency in a foreign language. Thai ranks in tier four of the five-tier scale, with a denotation (*) indicating it’s “usually more difficult for native English speakers to learn than other languages in the same category”:

And the stigma surrounding its nighttime use is backed up by awesome Bill Hader bits:

I think many also regard learning the language as pointless, as enough people on the Thai tourist trail speak English to make getting what you need and where you need to go a cinch most of the time.

Being far from prodigal with languages (or with studying anything), I set my expectations low heading in. But after five months of regular instruction and minimal outside-the-classroom effort, overall I’m pleased with the amount I learned and believe it will surely impress the waitstaff at a Thai restaurant back home someday (or uncover that they are actually Vietnamese).

Language Learning Background (For Context)

Age While Studying Thai: 28/29

Language Resume:

• English: Native

• Spanish B1 level (self-assessed): two disinterested years each in high school and college, studied at language schools for ~10 weeks total in Panama and Colombia in mid-twenties

• Have messed around with other languages on Duolingo, but never for long

Thai is the first language I’ve attempted to learn when starting from square absolute-zero. While I didn’t start taking Spanish until high school, growing up in America you pick up a fair amount of words and phrases through restaurant menus, movies, and Taco Bell commercials.

Even when studying Spanish a few years ago as a (de facto) adult, it was a labor of love. Sometimes I think I like reading about language learning and following polyglot exploits (like those of Benny Lewis and Laoshu) more than actually studying and practicing.

If I had any, my language learning strengths would be vocab memorization, reproducing the tone and inflection of native speakers, and reading. Weaknesses are nearly everything else involved, including listening and processing normally-paced conversations, remembering or at least implementing special grammar rules, and writing.

What I Knew About Thai Before My First Lesson

Since Duolingo’s Thai course is seemingly stuck in permanent beta mode, before going to Thailand I downloaded a free app called Thai by Nemo. Other than learning ‘hello’ (sawatdee) and ‘welcome’ (yindee), not much really stuck with me (probably because I never felt compelled to stick with it). Through reading the resources and posts on the r/languagelearning and r/learnthai boards on reddit, I also picked up that:

• Words can be one of five possible tones (middle, low, high, rising, falling)

• To be polite, guys say “krab/kap” at the end of sentences while girls say “ka”

• The ‘alphabet’ is 40+ consonants and almost half as many vowels

• There are no spaces in between written sentences

• Mai pen rai (roughly, “don’t worry about it”)

And that’s basically it.

Expectations/Goals Through Five Months

Since I didn’t know what I was getting myself into and because I was still freelancing, I set the bar fairly low. At the end of five months, I told myself I simply wanted to be able to:

• Have ‘restaurant fluency’ (be able to order food, ask about menu items, etc.)

• Ask basic questions in shops/bus stations (do you have this in a big size/color, when is the next bus)

• Be able to go through the ‘hellomynameisIamfromdoyoulikeithere’-s’ comfortably with strangers

• Explain that I am allergic to peanuts well enough to not die

Naturally, I also expected plenty of frustrating moments, days where I felt like I had learned nothing, and not really being able to read much after all was said and done. I also had the expectation that not many people in our town (~25,000) would speak English, forcing me to use Thai frequently in a variety of situations.

Method & Instruction

Although I prefer to learn most things just figuring it on my own, starting with a native speaker instructor seemed like the best option since I had zero foundation and none of the free materials I could find online presented the language in a progression that seemed logical to me (ironic foreshadowing).

During my five months of study I had two different kru, whose approaches were polar opposites of the other:

Teacher 1:

• Co-owner of a language center, spoke English fluently

• Taught with workbooks written solely in Thai

• Gave regular tests and homework on which my classmate and I were strictly graded

• Heavy focus on reading, perfect tonality, grammar, and spelling memorization

• Spoke in English often, but never wrote in it

• Classes were five days a week, 90 minutes a day for two and a half months. I had one classmate with me, who was also a complete beginner.

Teacher 2:

• Instructor at a different language center, spoke English and French fluently

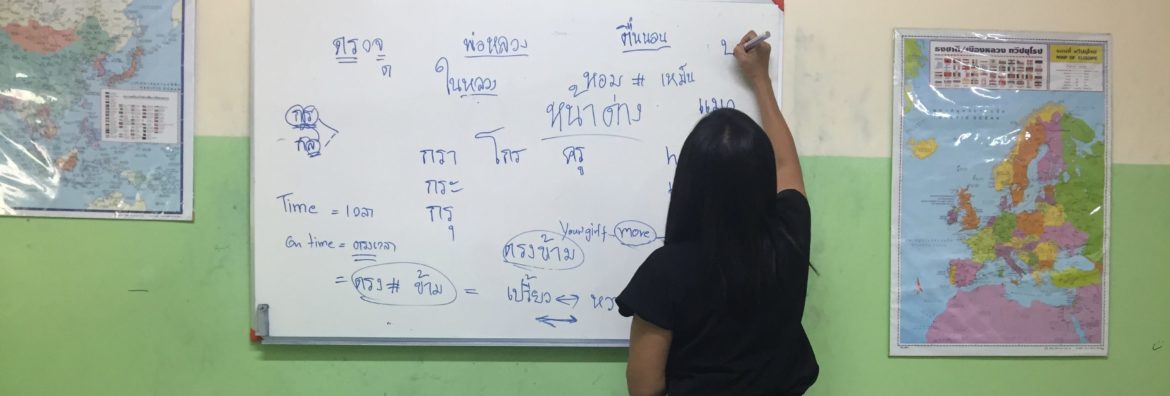

• Occasionally had me translating basic sentences off an (English) worksheet, otherwise everything done on whiteboard

• No homework, tests, or real formality

• Focused strictly on phrases and words I would find immediately useful

• Explained concepts in English and wrote most words and sayings karaoke-style (writing ‘sa-wat-dee’ instead of in Thai script)

• Classes were three days a week, one hour a day, for one and a half months. Classes were one-on-one.

Outside Resources:

Outside of class (and homework given by Teacher 1), I’d occasionally establish a routine of studying on my own, but nothing that ever stuck for too long. When I did study, I used:

• Memrise app (top 4000 most common words deck)

• Actual flashcards on words and phrases from class

• YouTube videos on whatever sticking point I was having

• iTalki just once, but loved it and found it very helpful

I also bought a children’s comic book as a way to learn basic dialogue, but never got past page one.

At the highest, I estimate I put in 5-7 hours of outside study during a week. However there were also many weeks I put in 0, especially during my stint with Teacher 1.

Methodology

Teacher 1 (Months 1-3):

It was impossible to know what Teacher 1 would be like heading in (I had to book the classes long before arriving in Thailand), but looking at the bulleted list above screams all sorts of learning red flags I know most successful language learners preach against.

A character flaw of mine is that I feel personally offended when I’m being taught something in what I feel is an impractical way, and my buy-in was admittedly low after the first few weeks when I recognized I was being taught the same way I was Spanish in high school: an emphasis on perfect grammar and spelling, rote memorization, and little practice speaking conversationally.

Being asked to memorize vocab words about gardening before I could ask for a side of rice felt… juvenile, as did being given quizzes and tests whose results were regularly referenced like they actually meant something other than being a gauge for how many random sets of words we could memorize. Mistakes were far from encouraged and my classmate and I were regularly told that Thai people would not understand us unless we perfectly executed the correct tone for every word we said (which turned out to be barely even a half-truth).

That said, because of Teacher 1, I can read more Thai than I ever thought I would be able to. While ‘read’ usually means being able to sound out words correctly without having any idea what they actually mean, even this came in handy more than a few times when looking at a Thai-only menu or map. I can’t deny that Teacher 1 gave me a solid foundation of the language that probably in part made my time with Teacher 2 so enjoyable and productive (spoilers).

Teacher 2 (Months 4-5):

I was a fan of Teacher 2 as soon as he assessed where I was and took into account why I was there: to learn to speak Thai with others. That and when I asked at the end of the first class if I had any homework, his look was reminiscent of the one I often gave Teacher 1 when she’d assign us pages of trace-the-consonant work to do at home.

While his persistent use of karaoke writing threw me off and may have slowed progress toward fluency [note]Pro language learners say this reinforces translating your target language from your old language, which is cognitively inefficient and keeps you from associating the word with its actual associated object or meaning. Tying it to the corresponding English word means it has to be translated in the head[/note] (if I were to keep studying exponentially), the amount I absorbed and was able to use outside of class skyrocketed. At first I thought all the karaoke might hinder my reading ability, but I quickly found myself recognizing new words (written in Thai) on signage that I learned in class.

Teacher 2 was extremely high-energy and our classes never had much structure other than they began with me asking how to say something, him answering, and then class spinning off into more related phrases and more questions from me. Grammar and tone were rarely ever taught directly. While with Teacher 1 I would reach the ‘brain melt’ stage of learning more out of frustration than actual learning, Teacher 2’s pace was so quick my brain often felt completely saturated by minute 45.

Self-Study and Practice:

Again, I never established a disciplined routine with learning on my own. Even though I can rattle off what expert language learners consider to be best practices (learn the 100 most common words first, decode the grammar structure, use mnemonic devices to memorize vocab) and was reasonably compliant with them when learning Spanish, for some reason I completely entrusted Teacher 1 to get me where I wanted to go. But by Week 5 I was already burnt out and rarely motivated to do much self-study (except to do better on her tests in order to avoid further ridicule, which I still didn’t do very well).

Taking the karaoke phrases Teacher 2 would write on the board and making physical flashcards with them was the most helpful in terms of rapidly absorbing words and phrases I could apply in the real world (even if it was delaying me from actually thinking in the language). These physical flashcards combined with mnemonic devices also helped with learning the consonants and vowels reasonably quick. Despite all the science backing up spaced-repetition learning, I never stuck with using flashcard apps for long (largely because making my own with the Thai keyboard was a slow process).

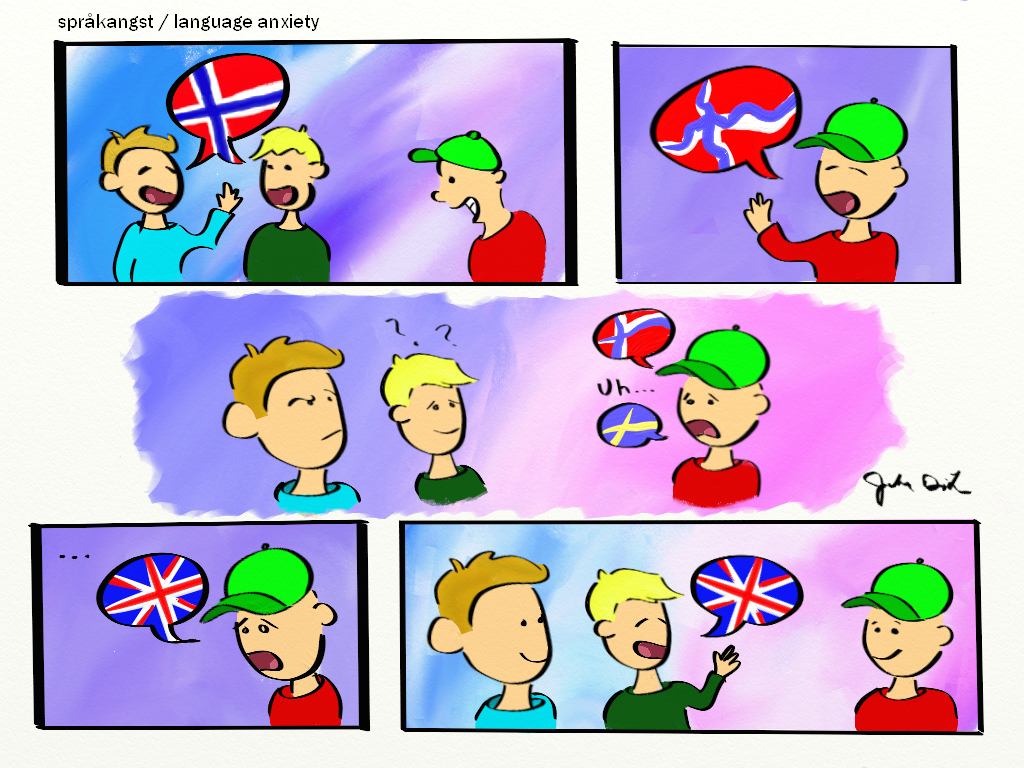

Even as my confidence and ability slowly improved, I fell into a rut with when and where I would use Thai. With so many more people speaking English than expected, I had quite a few of these interactions (substitute the Norwegian flags for Thai and pretend I’m the guy in the cool green hat):

Credit: reddit user Grandpa_Shorts

Generally, I stuck to using Thai in stores and restaurants, but very rarely did I ever try and make small talk. On the few occasions I did (usually at restaurants I frequented), the ‘conversation’ ended in an ‘aww that’s cute’ kind of bemusement or just a confused look on the other person’s face. I hit this exact same road bump with Spanish and can’t help but think taking a 90 Strangers-type approach with my next language (Japanese) would be a helpful workaround.

Results

Aaaand after five months here’s what I can do in Thai:

- Order food and ask about menu items with no confusion or struggle 90% of the time

- Read and understand a usually-helpful amount of words on signage and menus

- Pick out occasional words in announcements and in others’ conversations

- Say “Are there peanuts?”, “Please do not put peanuts on it,” and “I can’t eat peanuts.”

Due to being undisciplined with practicing them, my basic conversation question/answer skills don’t extend beyond what is your name, where are you from, and what is your job.

Overall, I speak enough that I feel like I pleasantly surprise many native speakers. I definitely do not speak enough where a Thai person who speaks English better than my Thai would not prefer to switch over.

Sticky and Not-So Sticky Points:

Teacher 1 grievances aside, there were many other elements of learning the language that made me consider giving up completely or otherwise question why I was even bothering. Heading in, there were also some things I was fearful of that turned out to be no big deal.

Tones: Overall, I didn’t think tones were that tough to get down (again though, I’m not even a medium-level speaker and maybe this is part of the reason why). Also, they’re not a completely foreign (puntended) concept as many make them out to be; even English can be tonal at times:

Generally, consonants will carry a tone mark telling you to use a high, low, rising or falling tone (sort of like how a flat or sharp modifies a note in music). If there is no mark, then most words are middle tone.

The most challenging aspect of this was when I was asking a question or was unsure if what I was saying was correct (so, a lot of the time). In English one way to indicate a question is to use a rising inflection, which in Thai completely changes the meaning of what you are saying (as it results in a rising tone).

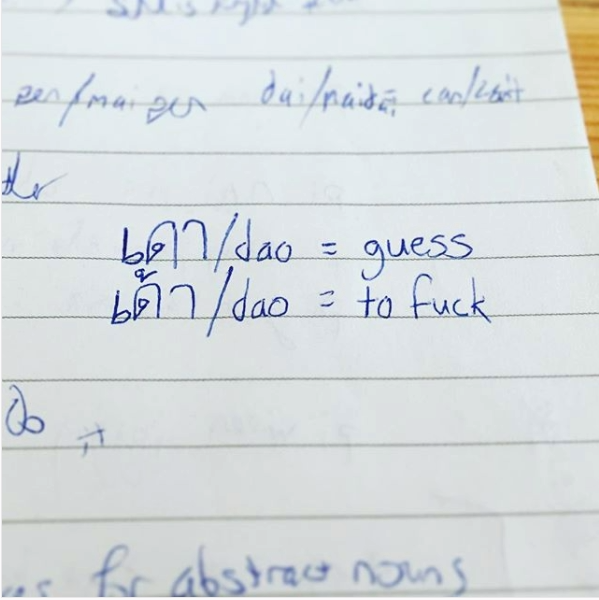

These tones and the short nature of Thai words can also lead to fun tongue twisters like: Krai kaai kai gai (Who sells chicken eggs?) and Maai mai mai mai mai (New wood doesn’t burn, does it?). They can also get you into some trouble:

Classifiers: You know how in English you wouldn’t say “two breads”, but “two loaves of bread” instead? Those are called classifiers and in Thai there are over 300 of them. And just for fun, they are often shared by groups of things that have no clear connection (descriptions from Thai-Language.com):

- ตัว / “tua” = animals, insects, fish, birds, tables, chairs, desks, shirts, pants, dresses, coats, digits and letters of different alphabets, parts such as nails

- เล่ม / “lem” = books, carts, candles, knives, swords, axes, pins, needles

- ชุด / “choht” = suits, sets of furniture, series of things, team of players

While intimidating and frustrating, I found that at least for purposes of ordering food in markets and restaurants, not that many needed to be memorized.

Google Translate: Even though Thai is generally spoken in short, simple sentences (comparatively), Google Translate blows. Unless you can explicitly identify which meaning of a word you want to use, it almost never structures or writes a sentence into something simple and comprehensible. Much more helpful was Googling phrases like “Thai phrases restaurant” and finding what I was looking to say on a Thai-teaching site.

Fonts: Even though I have a solid grasp with reading simple words and phrases, many consonants are simplified or stylized in a way that make them incredibly difficult to read/don’t look like anything I learned in class. While I learned to recognize some of these stylized versions, other times I was still at a loss even though I could read all the consonants in my textbook’s font.

Funky Sounds: Another reason Thai is thought of as so difficult for Westerners are its many unfamiliar sounds. In particular, the ng sound in words like ngaay (which ironically means ‘easy’) remains impossible for me, especially in the flow of speaking, where I tend to prepare my mouth for the awkward position by trying to make my chin one with my neck.

Telling Time: Both teachers tried to explain telling time to me, which in Thai is divided into six parts of the day instead of English’s two (AM and PM). I never even got close to grasping/remembering it, rationalizing by thinking about all the times I’ve never asked anyone for the time over the past decade.

Successes, Failures, and Favorites

Three Little Failures:

• Early on, I looked up how to say goodbye in Google Translate and it told me lah gawn. So naturally, I started saying this to store clerks, taxi drivers, and basically everyone else, all the time. One night, a 7/11 employee seemed alarmed when I hit her with a confident lah gawn, telling me in English: “no no no don’t say that!” Apparently, law gahn is how you say goodbye to someone you know you won’t see again or in a long time, meaning I had told about half the town essentially to “Have a nice life!”

• I once told a waitress that was concerned about my girlfriend and I going out in the rain, “I will have your umbrella” instead of “I have an umbrella.” Despite her confusion, she actually seemed willing.

• The head of the English program at my girlfriend’s school goes by ‘Kru Eh’. The word for banana is ‘gluay‘. The word for dick is ‘kuay.’ And that’s how I once asked someone if they knew a ‘Teacher Penis’ at my girlfriend’s school. This is also why one of Thai people’s favorite pastimes is pointing to bananas and asking you how to pronounce them in Thai.

Three Little Successes:

• On many occasions, I would go to a restaurant, order food, ask questions, and pay being understood 100% of the time. Again, this is what I practiced most but the look of relief from shopkeepers that I suspect weren’t confident in their English was very rewarding.

• That first time I realized I had told the lady at the smoothie stall my name, where I was from, why we were in Thailand, for how long, what are jobs were, and where we were going next, all in Thai.

• After ordering buns at a streetside stall, an old man behind the cashier-person said something like “That farang (Western foreigner) speaks Thai?” as I walked away.

Favorite Phrases:

• It’s said Thai people don’t really say any form of ‘how are you’ to one another, but instead “did you eat yet?” I don’t think I ever actually caught anyone saying this to each other, but it’s fun to say anyway: geen kao rue-yahng

• The Thai equivalent to “piece of cake” is “gluay gluay” (banana banana!)

• One thing I love about languages is that it’s often a clue to much more about the culture that uses it. Thai people are generally indirect communicators, so at the end of most requests it’s polite to stick in the wordnoi (a little bit), even if it doesn’t make much literal sense: puud fi noi krap (turn on the lights a little please), chuay keeyun hai du noi (‘can you write it for me a little’), kaw yuum deensaw noi dai mai krap (‘can I borrow a pencil a little please’).

Favorite Mnemonic Devices To Remember Words:

• Paw-kaa (pen): I pictured a dramatic scene where my pen ran out of ink so I cried out in butchered Spanish, “PAW KAWWWW”

• Sappan (bridge): P.K. Subban clumsily walking across a bridge wearing skates

• Prunee (tomorrow): Staying in a hot tub until tomorrow will surely make you pruny

If I Had To Do It All Over Again…

Hindsight makes everyone a genius, but I think the optimal approach to have optimized my learning time in Thailand, with or without a teacher would have looked like:

- Weeks 1-4: Focus on learning the consonants, vowels, and basic principles of tone first (visually and verbally)

- Weeks 5-8: Learn and practice the ~50-100 most common words and phrases (verbally, karaoke, and Thai script). Focus on simply being understood, with perfection a secondary concern

- Weeks 8-12: Take already-learned words and phrases as well as some new ones to learn the basics of sentence/request/question structure

- Weeks 12-16: Ditch the karaoke writing in place of Thai script only, focus on cleaning up tone other nuances, and using different tenses

- Weeks 16-20: Vocabulary/phrase expansion

Throughout, I would better force myself into more uncomfortable speaking situations with people I knew wouldn’t try and switch to English. I think weekly iTalki sessions rotating between two or three different instructors would have been a boon as well. And even though people swear by them, I think I would ditch the flashcard apps for paper ones much quicker.

Final Reflection/TL;DR

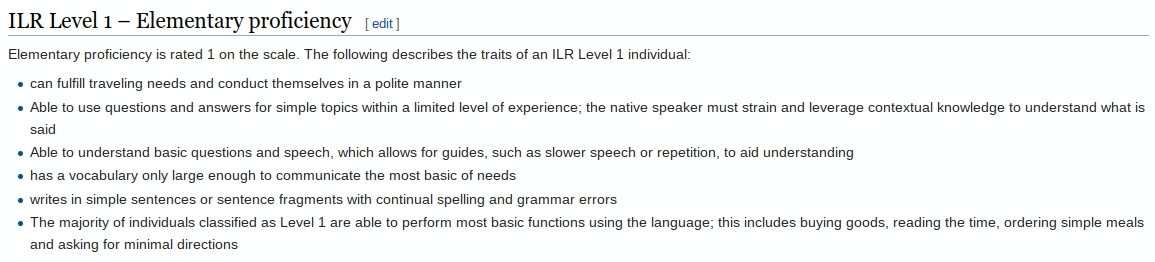

Again, fluency in Thai is not even on my radar (or the rader next to my radar), and most basic conversations at normal speed are still beyond my grasp to both listen to or participate in. Looking at the Interagency Language Roundtable scale, I am definitely not higher than ILR Level 1 (Elementary Proficiency):

This might not seem like a lot for five months (and it isn’t). But even with some huge knowledge gaps still in my basic survival Thai, that I had other things going on (e.g., freelancing and having a girlfriend), and one teacher pushing me to the point of wanting to quit out of (immature) spite, I can’t help but be pleased with what I did manage to learn and the reactions I received after just five months of just dabbling in the language.

It sounds obvious, but Thai was also a reminder of just how much hard work, patience, and persistence learning a language takes; I took for granted the foundation that the four years of Spanish gave me before I really started giving it a real effort. As I am already in the midst of my next language-learning foray (Japanese in Japan), I’m trying to keep this in mind and am sure and that one day I’ll look back on the time spent learning Thai simply as a re-education on how to learn, long after I fail to keep my sa-bai-dee mai’s (how are you?) straight from my sawatdeekap‘s.

I’d like to reemphasize that I am by far a quick learner when it comes to this kind of stuff and I also have a pretty short attention span. I can’t help but think that someone similar who is staying in Thailand, starts with a decent teacher and has the gumption to study on their own even just an hour a day could approach a medium-to-high level of proficiency in the same amount of time, especially if it was one of their sole purposes for coming to the country.

This all might seem like a lot of words just to say: “You can learn Thai if you actually try!”, but given the language’s reputation (well, half of it), I hope it can convince someone on the fence that if they go about it in a way that makes sense to them, learning Thai can actually be gluay gluay and an extremely rewarding experience.

—

I just spent 5 months in Thailand and I must say that I am in about exactly the same place you were in at the 5 month mark. I really thought I’d be closer to fluency at this point. But, everyone I have spoken to says it takes at least a year for a native English speaker to feel some comfort level with Thai. Even those of Asian decent have stated they feel it takes nearly a year, with real fluency taking many years.

Thanks for the comment Trina and I’m glad to know I’m not alone! What’s more is that after writing this post I moved to Japan and began studying Japanese, meaning I promptly forgot almost all the Thai I learned. I enjoy Japanese and have made decent progress with it, but can’t help but wonder where I’d be if I had just stuck with Thai.

I’ve been in Thailand off and on for three years studying Thai off and on while here. It is so difficult! Yet, I speak way more than many of my expat friends. Most people give up. Kudos to you for doing it. Have you studied any langauges since, and if so, did this experience help?

Hi Jeff, thanks again for reading and the comment! When I left Thailand I actually moved to Japan and lived there for 15 months. I don’t know if it’s because I was there for a longer period of time or because I was interacting with Japanese people for 8+ hours every day (I taught English whereas in Thailand I worked remotely), but I found Japanese waaay easier. A big part of that I think is simply because of ridiculous amount of good resources out there for learning Japanese, whereas I couldn’t find a single one for studying Thai that I enjoyed using. Also, there’s no tones in Japanese which was one of my big downfalls with Thai.

Although Thai and Japanese couldn’t be more different, I think learning Thai got me comfortable with learning new alphabets, and got me in the habit of creating pneumonics to help remember all the new letters and characters.

Sadly, since I moved to Japan immediately from Thailand, I pretty much forgot all the Thai I learned (including most of the alphabet). But I intend to stick with Japanese back in the US!