There is never an absolute answer to everything, except of course that you have to do your squats.

-Mark Rippetoe, American strength coach and author

—

More than any other exercise, none has been more vilified- or misunderstood- than the squat.

Which is massively ironic considering that people- especially those with desk jobs- perform multiple squats every waking hour of their life.

Getting up from your office chair, out of your car, or even off the toilet… if you are going from a sitting position to standing or vice versa, you are squatting.

Why wouldn’t you train a movement that has a direct carryover to your everyday life?

—

Like barefoot-style running and diet, squatting is another one of those things that humans did one way for a million years, and now that we’ve changed it up in the last few hundred we have a plethora of new maladies.

Unfortunately with squatting, the solution to the problem isn’t as simple as orthopedics or medicine, but surgery.

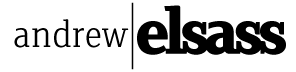

Squatting to the ground is a natural range of motion for our species, and the natural position in which to relieve oneself. There is a reason toddlers go into a squat when they are beginning their potty training or picking something up off the ground– it’s how our bodies are designed.

The sitting toilet as we know it is unique to Western society (a few European nations being notable exceptions), and surprise- there are lower incidences of colon and pelvic disease in nations that use a squatting method to go to the bathroom.

Around the time the sitting toilet became in vogue in Victorian England and eventually the rest of Western civilization, so too did appendicitis, irritable bowel syndrome, colon cancer, and other fun diseases known mostly only (even today) to squatting nations.

The short of it is that our organs don’t empty themselves completely and properly when sitting versus squatting- consider gravity for even a few seconds and you’ll get the picture.

How could this movement ever possibly be a detriment to your health?

—

While tearing out your commode might not be a realistic solution, there is another way for our bodies to reclaim the flexibility and range of motion that gets lost by sitting all day: with a barbell, of course.

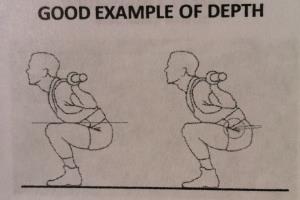

When a squat is done properly (i.e. with the hip crease going to parallel, or below, if possible), virtually the entire body is being strengthened from the ankles through the abdomen through the arms that are securing the bar against the back. And of course the quadriceps, hamstrings, and glutes get their fair share of the load, too.

Contrary to the popular misconception that squats are bad for your knees and back (which is ridiculous- when a squat is performed properly most of the force is taken in the hips anyway), the movement has been said to prevent and deter injuries by way of strengthening the stabilizing muscles, ligaments, and tissues that surround the knee.

Where did these misconceptions come from? Similar to many of the myths that have become ‘conventional knowledge’ in the world of diet, many believe deep squatting is bad for your knees and spine because of some bad science that has been perpetuated for decades, despite studies proving the contrary.

When injuries occur while squatting, the cause is usually from the athlete only going into a partial squat. In these, only the quadriceps are activated and the movement never reaches its natural conclusion, forcing the knees to absorb a tremendous amount of stress in order to halt the movement.

Conversely, in a full depth squat, the hamstrings and glutes are activated when the hips drop below parallel, which in turn balance out the load distribution evenly on both sides of the knee.

Partial squats are also the source of the myth that the movement is bad for your spine. Rippetoe:

“Another problem with partial squats is the fact that very heavy loads may be moved, due to the short range of motion and the greater mechanical efficiency of the quarter squat position. This predisposes the trainee to back injuries as a result of the extreme spinal loading that results from putting a weight on his back that is possibly in excess of three times the weight that can be safely handled in a correct deep squat. A lot of football coaches are fond of partial squats, since it allows them to claim that their 17 year-old linemen are all squatting 600 lbs. Your interest is in getting strong (at least it should be), not in playing meaningless games with numbers. If it’s too heavy to squat below parallel, it’s too heavy to have on your back.”

Like with any new exercise, start slow and with light weight. Even if you are just squatting with your body weight or an empty bar in the beginning, you are guaranteed to be sore in the days following, and your strength gains the next time you go to squat (or to stand up) will be more than apparent.

In lieu of keeping this post a readable length, squats will make athletes (and anyone) more explosive, give them stronger abs and core strength, increase their vertical, increase bone density, make them more flexible, run faster, help achieve normal hip function, and of course give them a bomb ass.

Essentially it makes anything you could possibly do, in or outside the gym, easier.

Even if your athletic focus is on more cardio-oriented sports like running or cycling, cross training with squats is going to be incredibly beneficial. If, in the case of running and cycling, your power output on every stride or pedal is X, and that power is coming from your quads, hamstrings, and the rest of the posterior chain, doing something to increase the output of that X variable is only going to make you faster at your given discipline.

To cite Rippetoe one last time, “All other things being equal, the stronger athlete always wins.”

—

Anecdotal evidence: When I lived in New York for six months I didn’t make enough money to join a gym, so my workouts had to consist mainly of body weight exercises and running. While I would throw in air squats from time to time, it wasn’t enough.

After a few months of being away from a barbell and squatting, I couldn’t even run anymore as the pain in my right knee became too unbearable for me to jog for longer than a minute. My knee had become weak.

How do I know that was the problem?

Fast forward to after I had moved back to Ohio and was again on a regular squat routine, I tried running again after a month or two and was able to crank out four miles without a hint of knee pain.

The problem is not with the squat. It’s with the sit.