10/24/18 Update: This post has been featured/republished (and made a whole lot prettier) on AthleticDirectorU.com: check it out.

This is the full-length, annoyingly-long version of my proposal to improve non-conference scheduling in FBS college football. It’s damn long, I know—to just get the general gist, check out the much shorter summary. Throughout the piece, I reference this spreadsheet; it’s embedded in section three, but still might be handy to have open as you read along.

Shoutout to SB Nation’s Bill Connelly for planting the seed this idea grew into.

Contents

- The Problem

- Proposed Solution: Draw Scheduling

- Sample Draw For The 2018 Season

- Pre-Mortem: 10 Problems, Possible Solutions, and Things I Haven’t Figured Out

- Conclusion/Call For Help

***

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]t’s no secret that college football has problems. Like, a–shit–ton–of–problems. Ask casual college football fans to rattle off things the sport gets wrong and non-conference scheduling might be far down the list (if mentioned at all).

And rightfully so, as this four-game stretch of the season isn’t negatively affecting anyone’s life or livelihood. But while many of the big issues will (sadly) require a slow-moving culture shift to truly be changed, non-conference scheduling is something that can be tweaked to increase the sport’s overall competitiveness, parity, and entertainment value, all without changing how it operates behind the scenes too drastically.

The heart of the problem is that in a sport with a 12-game regular season in what is essentially a 130-team league[note]Well, 66 if we’re being honest with ourselves[/note], the out-of-conference season is scheduled by the schools themselves, and not by a central body. This structure breeds imbalances affecting not only the outcome of seasons, but further fuels the class struggle between the teams in its Power 5 (ACC, Big 10, Big 12, Pac 12, SEC) and Group of Five (AAC, CUSA, MAC, Mountain West, Sun Belt) conferences.

Fans are more or less aware of the consequences: non-con scheduling is a source of debate every late November-early December and has altered the course of several seasons in the BCS/CFP era (often at the expense of non-traditional power programs). That teams in some conferences play nine conference games and three out-of-conference opponents while others play eight and four has also been heavily scrutinized[note]And per the ‘Hawaii Exemption’, schools playing Hawaii (and the Rainbow Warriors themselves) can schedule a fifth non-conference game[/note].

Like most of college football’s issues, the source of the problem is complex and multi-faceted. However, it can be broken down into two source problems:

Problem No. 1: Premature Scheduling

—

Non-conference schedules are made comically in advance.

As of September 2018, Ohio State has a scheduled home and home with Boston College for the 2026/2027 season, Mississippi State and Texas Tech are playing in 2028/29, and Notre Dame is slated to host Clemson in 2034, or about the time current high school football top recruits will be in their mid-thirties[note]I know this last one is treated as a de facto conference game, but why schedule so far in advance when another wave of conference realignment by then is inevitable?[/note]. While these long engagements do sometimes dissolve before they come to fruition, more often they are far-flung bets that the opponent will stay a legitimate (but sometimes not too legitimate) matchup in five, 10, or 15 years and will offer some combination of a winnable game, attractive opponent, and resume booster come selection Sunday.

H/T: FBSSchedules.com

Sometimes these matchups flop majorly due to a program’s natural ebb and flow: Cal was a perennial 8-10 win team in the early 2000s when Ohio State scheduled them for a home and home deal in 2012/13. By the time the series actually rolled around, the Golden Bears were in the middle of a 4-20 (how Berkley-appropriate) dry spell.

Other times, schedules shake out to just be too damn difficult for a team eyeing a playoff spot, reportedly the reason Michigan paid Virginia Tech a $375,000 cancellation fee over their planned 2020/21 series. Changes in conference schedules can also impact out-of-conference matchups, the reason why Wisconsin backed out of a 2018/2021 home and home with Washington. And sometimes they’re nixed because something better comes along, as Nick Saban told the Lansing State Journal in 2015 about why the Crimson Tide canceled a 2016-17 series with Michigan State:

“For business reasons, we have played neutral-site games to start the season,” Saban said. “And when you play a home-and-home – which we played Penn State home-and-home a few years ago — when you play at home you do really well (financially), when you play away you don’t do very well. When you play a neutral-site (game), you do very well every year. We wanted to try to play the series, instead of home-and-home, at neutral sites. And we had other opportunities to play other teams at neutral sites. So from a business perspective, our administration chose to do that.”

Scheduling this far ahead also somewhat depends on not having another massive wave of realignment (which is almost assuredly coming in the next five years) that could turn some of these non-cons into straight up cons.

Whatever the reason, hyper-advanced scheduling prevents more exciting matchups between two teams of the here and now to occur more consistently.

Problem No. 2: Chickenshit Scheduling

—

Simply, FBS teams schedule FCS schools or from the bottom of the FBS barrel for what is (usually) an easy win, a tune-up for their players, and all the financial benefits of a home game. In return, the visiting team gets anywhere from $300,000 to a cool million (sometimes more revenue than they’d generate for a home game) and some TV exposure.

Although your team playing an FCS school can feel like a waste of a college football weekend from an entertainment standpoint, FBS-FCS matchups are important for funding and keeping football alive at the lower level and in turn the levels below that. Provided you don’t fuck it up, an FCS win is largely viewed as a bingo free space that doesn’t (as we’ve seen so far) help or hurt a (P5) school’s CFP chances.

While these are usually de facto warm-up games scheduled within the first few weeks of the season, some conferences like to[note]Intelligently or annoyingly, depending on who you ask[/note] schedule FCS opponents inside the final month of the regular season as a sort of breather date before rivalry week and the postseason, the same time those in most other conferences continue to grind through the thick of their conference slate.

But that’s only a minor annoyance, and one I can live with. The real problem is that there’s no incentive for top P5 teams to schedule top G5 teams, and it seems like many actively avoid any proven giant killer. For much of the college football collective conscious, G5 schools do not belong on the same field with their P5 brethren (despite the on-field evidence showing the contrary).

Couple this with that of the 40 bowl games played in the 2017-18, only seven of them pitted P5 against G5. P5 fans want to see how their school stacks up against other P5 schools (but if they do face a G5 team and lose, they’ll have a litany of excuses at the ready[note]Including such favorites as “They just couldn’t get up to play an inferior team”, or “They were drained from playing a real conference schedule”[/note]). As Bleacher Report’s Todd Kaufmann put it, P5 conferences would rather have a cheap win (against FCS and the weakest G5 schools) than an expensive loss to a still-seemingly “inferior” top G5 school. This essentially makes FBS a two-division league with little and only carefully-calculated crossover.

A textbook example[note]Also see 2006 Boise State, 2008 Utah, 2010 TCU…[/note] of how these imbalances can cost a team came last year in 2017. Despite going undefeated through the regular season, the University of Central Florida Knights did not get a chance to play for the National Championship by being selected into the College Football Playoff.

Although the CFP Committee is not in the business of outright explaining any of their decisions, the blame for their occlusion went to their schedule: depending on what strength of schedule rankings you looked at, #4 seed Alabama had a Top-10 schedule while UCF’s was anywhere between 50th-90th.

For the anti-UCF/G5 crowd, the solution was a snide “schedule better teams” or illogical “join a better conference”. For those who thought UCF deserved a spot (or at least a final CFP-ranking higher than 12th and certainly one ahead of schools with two and three losses), the solution was any combination of expanding the playoff and adding automatic berths for all conference champions, or giving playoff autobids to any undefeated G5 team[note]none of which I am opposed to[/note].

Based on what we’ve seen in the CFP’s first four years of existence, the only hope for a G5 team to pip a CFP spot is to go undefeated, play a murderers’ row out-of-conference schedule, and pray for chaos in the form of every title contender dropping two or more games. According to CFP executive director Bill Hancock, “To qualify for the playoff, teams need to play tough schedules against good teams—that is the way for all teams to stand out and be ranked high by the committee.”

The illogicies with this are painful:

1. Teams can’t help it if the rest of their conference is weak overall, and joining a stronger one is a little more than just filling out an application on the SEC’s website. To paraphrase one of Connelly’s books, today’s power conferences are largely dictated by which universities were chummy 60-100 years ago, making teams like UCF victims of low-key collusion.

2. Those top P5 schools whom a win over would provide a boost to a G5 team’s CFP hopes? They have no need to schedule such opponents because A) their conference schedules provide a nice base degree of difficulty compared to G5’s; and B) Scheduling and losing a non-conference game with a big-time program is seen as forgivable, whereas losing to even the best G5 school can be seen as a blemish on what should have been a win—in other words, there’s little upside and much downside.

You may indeed only be able to play the schedule you have, but why not take measures to make everyone’s slate as strong or as weak as the next school’s? While a P5’s conference schedule will always give them an overall SOS edge over a G5’s, stop allowing the former to hide from the latter and at least attempt to give some equilibrium to a teams’ three to four non-conference games. And for the love of god, stop scheduling games more than a year or two in advance[note]If ADs and other influencers dare cry “But logistics!”, they need to ring up the schedule makers of other sports (many of which occupy arenas and stadiums with multiple pro tenants plus a revolving door of major events—college football stadiums by and large sit dormant the entirety of the college football season, waiting for those 6-7 Saturdays): The NBA and MLS release their schedules about two-to-three months before their seasons begin, the NHL four months prior, the NFL five months, and Major League Baseball releases their gargantuan 2,430 game season slate about 6 months in advance. I imagine part of the reason college football insists on scheduling matchups currently-unborn generations will enjoy is due to simple accounting and being able to get some sense of what kind of income they’ll be working with that fiscal year. But there’s no reason the same amount of money can’t float around in a structured (dare I say socialist?) system, and in a standardized way (e.g., X million for top-tier matchups) that would still provide accurate-enough estimated revenue.[/note].

I believe this madness can end, and that balanced non-conference schedules can be created in a timely fashion while still preserving the P5-G5-FCS flow of money and still giving schools the option to play neutral site games.

…

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]any propose taking soccer-style promotion and relegation and applying it to college football as a solution to the sport’s stratification problem. While this is mine and many fans’ wet dream, it’s somewhere below paying players and the video game coming back on the list of things likely to happen anytime soon. But perhaps some sense of scheduling parity can be reached by borrowing another of soccer’s signature non-game events: the tournament draw.

For major soccer tournaments like the World Cup, a lottery is held which places the 32 qualified teams into eight groups (named A-H). The teams in each group are drawn out of four pots: Pot A contains the tournament’s host along with the top ‘seeded’ nations so they can’t play one another in the group stage, and then teams are distributed by descending rank into Pots B, C, and D. As teams get drawn out of each pot, they are placed sequentially into the groups of four, although there are stipulations to prevent too many teams from the same continent being pitted against each other.

It’s not perfect, but overall this format produces a tournament schedule ensuring competitive and geographical balance, transparency, and the right amount of quirky and random matchups. It also lends itself well to a dramatic TV spectacle complete with ritzy settings, celebrity hosts, guest pickers, and plenty of analysis and reaction.

Although the perfect solution would be to leave scheduling up to impartial individuals (or ‘scheduling czar’ as Connelly puts it), relinquishing scheduling duties to this style of draw would produce fairer schedules while also embracing the sport’s love of attention and spectacle.

Selection Saturday

—

Imagine.

It’s early April. Recruiting is in a quiet period, March Madness is over, the NFL Draft might be in its prognostication parade but is still weeks away, and early round NBA and NHL playoffs aside, the weekends are largely unclaimed from a sporting calendar standpoint. It’s Saturday night, and you are taken live to Phillips Arena in downtown Atlanta. Even though the Hawks’ season may still be going, tonight the 21,000-seat arena has been converted to a stage for college football’s biggest off-season event.

Part school-specific tables, part awards show-style delegation, the floor of the arena is a college football who’s who. Head coaches[note]who will be jetting to all parts of the country the following weekend for the spring evaluation period[/note], ADs, celebrities, and for the hell of it, mascots mix and mingle on the floor below fans happy to make the weekend an excuse to travel someplace warm. As the host school, Georgia Tech’s Yellow Jacket Marching Band fills time before and after commercials with stand tunes. Tech, of course, won these hosting rights through a bid process, awarded each year by an organizing committee.

At one end of the arena is a stage showcasing four large oversized and overturned helmets, each sporting a different color and sitting on a small pillar bearing one of four labels: Allstate Tier I; Nissan Tier II; Taco Bell Tier III; Dollar General Tier IV.

Above the stage hangs the logo of the 2018 CFB Scheduling Convention, hued navy blue and buzz gold, bordered by banners of the NCAA, CFP, and each FBS conference. Below lies a giant electronic grid that’s part-NBA Draft board, part-Vegas sportsbook menu. On it rests the names of all 130 FBS schools. Next to each school lies four empty slots which will all be filled in by the end of the night.

The arena noise slides into decrescendo and out on stage walks the night’s host and first guest picker: CFP chairman Kirby Hocutt. Just before reaching a hand into the helmet marked Tier 4, he announces:

“Atlanta and the rest of college football world, welcome to the 2018 College Football Scheduling Convention. As defending National Champions[note]*[/note], the University of Alabama Crimson Tide will begin the 2018 college football season by playing…”

The System

—

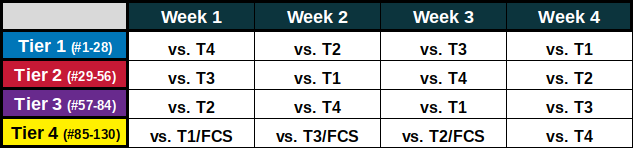

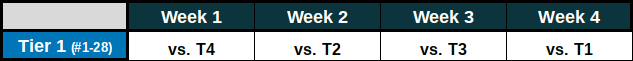

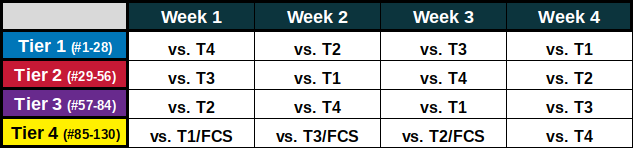

At the end of the college football season, the 130[note]For simplicity’s sake, I am counting currently-transitioning Liberty as FBS[/note] FBS teams are divided into the four aforementioned tiers: 28 teams in T1, T2, T3, and 46 in T4. Which ranking system is used—Sagarin, S&P+, or other—is largely irrelevant as they will all place teams roughly in the same four groups of 28/28/28/46 with little deviation. Last year’s CFP playoff teams are seeded 1-4, but from there the teams are sorted in descending order purely by ranking.

This ranking serves as the procedure’s pick order. Each tier will match up against another designated tier each week of the non-conference season.

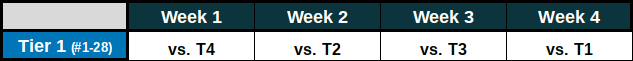

For instance, Tier 1’s non-conference schedule is determined by drawing opponents[note]A system would be in place to prevent drawing an opponent from the same conference[/note] from their respective pots in this order:

After beginning the season with a cupcake, T1s then navigate an up-and-down increase in opponent quality through the rest of the non-conference slate. Week 4 could instantly make a claim over rivalry weekend as the sport’s biggest, as every Tier 1 team is pitted against another in a BracketBuster-for-major buffet of games.

For those wishing to play neutral site games, stadiums could reach agreements with certain teams in advance and then just write in the opponent after the draw, provided the other party agrees to the proposed sum.

A steady increase in the quality of competition also increases the likelihood of seeing big boys face each other when they are in full gear as opposed to the opening weekend “blockbuster” games which often disappoint and see one or both teams without rhythm.

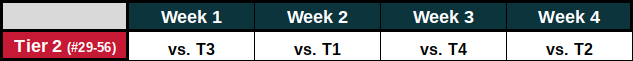

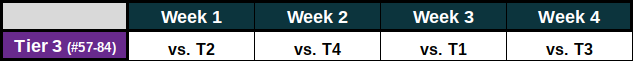

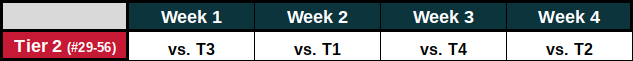

Teams in Tier 2 face similar opponent variability from week to week.

The season opens against a team deemed a notch below, followed by a big T1 matchup in Week 2. A recovery period follows in the form of a T4 game, followed by even matchups against fellow T2s (further adding to the insanity of Week 4; see more on that weekend below) to conclude the non-conference season.

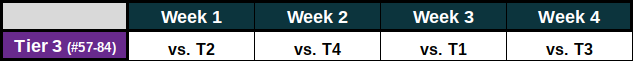

From here, the schedule fills itself out.

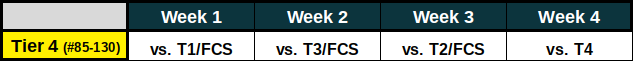

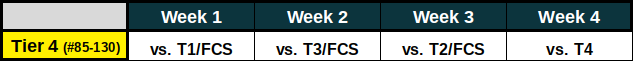

Since Tier 4 is double the size of the other tiers, scheduling is not as simple. To ensure the FBS-FCS cash still flows, every T4 team will play one FCS team[note]Due to the number of FBS teams and how I structured my tiers, one T4 team has to play two FCS teams (I think). In my sample draw this ended up being Charlotte. Someone smarter than I could probably figure out a better workaround.[/note].

Their group being double the size of the others, every T4 team can’t mathematically face an opponent from each of the other three tiers. Instead, they’ll play two games against some combination of T1-T3s, an FCS team, and one-to-two fellow T4s. In the event a T4 only draws one matchup with T1-T3s and has a hole in their schedule (that can’t be filled with another FCS team), T4s pair up for another game together[note]I only had to do this a few times—there may be a way to math out of this but that’s where I ended up.[/note].

These FCS games would still count toward bowl eligibility as usual, aiding in parity and possibly helping G5 conferences earn more bowl appearance revenue (there’s a downside to this though; see Pre-Mortem section) by being a boost toward six wins. I imagine the scheduling of these games could be left to the schools in order to encourage more regional matchups and keep transportation costs lower. Playing against an FCS school and possibly more than one T4 lightens the load for these rebuilding teams, possibly encouraging some churn into T3 (where they’d get a schedule fans are probably more excited to see) the following season.

—

No matter how you divvy up the tiers, there’d be some quirks. But this system still produces non-con schedules far more balanced than the current free-for-all of mismatched and uninteresting matchups making up a large chunk of the offseason slate.

Despite their implied status, the tiers don’t really mean anything. Sure, having three weeks to collect film on and prepare for your biggest non-conference opponent is a nice perk of being in Tier 1, but since Tiers 1-3 all play opponents from the same pools, any huge discrepancies between team’s non-con schedules should hopefully be diluted enough to not be a talking point come Selection Saturday[note]I am speaking generally here—since the team rankings are merely projections, draws will shake out to be softer or more challenging than expected and people will inevitably still bitch about how someone ain’t played nobody come CFP Selection Sunday (but hopefully less so). Draw scheduling may not be a panacea, but at the very least it’d be a good-enough antibody.[/note].

Draw scheduling also produces intrigue in the same way March Madness does, pitting together two seemingly unrelated teams that quickly becomes a matchup you are dying to see for the sheer randomness of it all and that it would never be scheduled of the schools’ own accord.

Other Reasons Why It’d Be Awesome

—

• Everyone Gets Their Shot: Your Boises, Houstons, and other G5s-of-the-moment would all get a game against a (projected) top-tier opponent to prove themselves, every year. With the right draw in the right year, I imagine this could ever-so-slightly increase the chances of a G5 school crashing the CFP party.

• Watch Party/Live Look-In Potential: It’s NCAA Tournament Selection Sunday-type drama meets slot machines, along with some vague elements of promotion/relegation thrown in. Plus, it’s a real reason to get excited about college football in the spring.

• Pro/Rel: Using postseason rankings to determine tiers could mean season-long drama as teams battle for what ostensibly would be promotion/relegation. As mentioned already, I’m not sure yet what the exact incentive is for moving up to a higher tier, beyond T1s get three weeks to prepare for their biggest non-con game.[note]There’s more about this in the Pre-Mortem section, but one thought is there could be some sort of financial incentive paid by the sponsors of each tier (in exchange for what, I’m not yet sure—a corporate patch on each team’s jersey during non-con games?)[/note]

• Bama Chips: A fun idea would be to give each team 1-2 ‘veto’ chips they can play if they draw a matchup they find unfavorable in exchange for another random draw. These could increase intrigue and add an element of strategy to the system (but might also decrease the speed of the process due to ADs, coaches, and whoever else congregating after every single selection).

• Flexible Scheduling: Instead of designating which weekends are for non-conference play, teams could have the freedom to schedule their assigned opponents whenever they see fit between a specified date in August and the first weekend in December. This would allow schools to plant flags on days where there is little other TV competition, such as on Thursday and Friday nights, Week ‘0’ in August, or even in mid-season gap in conference play.

So if we had used this system for the 2018 non-conference season, what would the schedules look like?

…

[dropcap]U[/dropcap]sing Bill Connelly’s 2018 preseason/spring S&P+ projections[note]S&P+ is an analytic system created by SBNation’s Bill Connelly that looks at play-by-play data and rates teams based on drive efficiency, explosiveness, field position, turnovers, finishing drives, and is adjusted for opponent. Read more about it here. The preseason S&P+ projections also factor in recruiting and returning production.[/note] (with the exceptions of slots 1-4, which I gave to last season’s playoff teams) for team rankings and a random number generator, I ran a mock schedule draw which can be seen in this spreadsheet or embedded here:

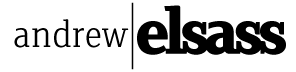

Key:

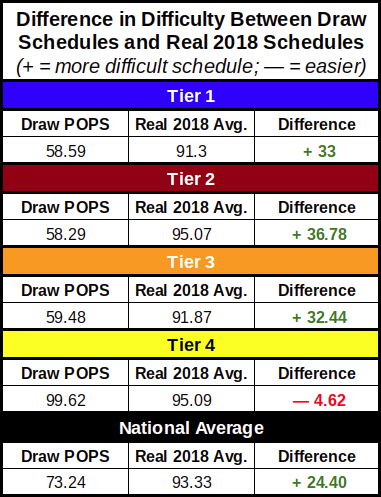

• POPS Avg.: Perceived OpPonent Strength Average. Just a shorter way of saying the average S&P+ ranking of a team’s nonconference opponents.

• Real 2018 Avg: Average S&P+ opponent rank in team’s real 2018 noncon schedule.[note]The Big 10, Big 12, and Pac 12 play only three out-of-conference games, and a few teams each year play five due to the Hawaii Exemption.[/note]

• Diff.: Difference in difficulty (according to S&P+ rankings) in a team’s real 2018 non-conference schedule compared to the draw produced-one: (Diff. = S&P+ opponent average from real 2018 noncon schedule – the same average taken from simulated schedule draw). A negative number indicates the draw-simulated schedule would be easier than their actual 2018 noncon schedule.

Listed from left to right are S&P+ rank[note]Again, save for spots #1-4, which I gave to last year’s CFP teams)[/note], school name, conference, then opponent rank and name for each of the four non-conference weeks. Following that is the POPS average rating for both the simulated draw and their actual 2018 OoC schedule, and the difference between the two (see Key above). None of this takes into account whether a game is home or away, something I haven’t quite figured out yet (see Pre-Mortem section).

Let’s unpack some of these schedules.

Tier 1

—

In Tier 1, the overall POPS average was 58.59, with the most difficult slate belonging to Clemson (50.5):

[table id=23 /]

Challenging? Compared to the non-con schedules we are used to, definitely[note]Bear in mind I wrote this in the summer of 2018–as of publishing three weeks into the season I don’t think Clemson would break much of a sweat with a slate like this. Unheard of? Intentionally or not, each year a handful of schools play a non-conference schedule of this caliber[note]A hunch the POPS analysis for the actual 2018 non-conference season confirms[/note].

More exciting for fans of all schools involved? In my eyes, hell yes.

But is this grossly unfair to what Georgia and their tier-lowest POPS average (66.75) drew?:

[table id=24 /]

The Dawgs lucked out with all G5 schools, but it’s still no walk in the park. Like Clemson’s, it’s not too different from what P5 teams actually put together for themselves.

How do these schedules compare to #20 Stanford’s, whose POPS of 57.0 is Tier 1’s median:

[table id=25 /]

Slates like this get me excited (granted maybe just because this is my project), but this looks typical of most teams’ schedules within my experimental draw. Many matchups feel like they could be weird but fun bowl game tilts, some possible traps, and a big opponent in week four.

Week Four: Showdown Saturday, Judgement Weekend, or Some Other Inevitably Wrestling-PPV-Esque Name™

—

Speaking of week four, let’s look at just how game-changing having an OoC showcase week like this would be.

For 2018, week four of the college football season comes in the fourth weekend of September (that Saturday being 9/22). MLB is winding up their regular season, the NBA and NHL still dormant, and the NFL season still so young that a Thursday-Saturday stretch of college football’s top 20% playing against each other would dominate the national conversation the week of and after[note]If you wanted you to completely own Labor Day weekend instead, you could move T1 vs. T1 week to the beginning of the month for a Thursday thru Monday smorgasbord (although these schools would probably be more adverse to playing each other the first week of the season.)[/note].

What it looked like in my draw (assigned days are my vision):

Thursday

Utah (28) vs. Virginia Tech (21)

Oklahoma St. (19) vs. Mississippi St. (14)

Friday

Texas A&M (24) vs. Wisconsin (12)

TCU (22) vs. Florida St. (18)

Saturday

Stanford (20) vs. Michigan (10)

Ole Miss (25) vs. Notre Dame (8)

Penn St. (9) vs. Oklahoma (3)

Texas (27) vs. Miami FL (13)

Oregon (23) vs. Alabama (1)

USC (15) vs. Clemson (4)

UCF (17) vs. Georgia (2)

Auburn (7) vs. Ohio State (5)

Boise St. (26) vs. LSU (16)

Michigan St. (11) vs. Washington (6)

Pretending for a moment the S&P+ rankings I’m using correspond with hypothetical AP ones, that’s eleven Top 25 matchups in a single weekend. Looking back at each of the 2016-2018 seasons, you have to extend a running count into Week 4 to reach the same total of amount AP Top 25 matchups, and into Week 5 for 2015.

This draw even feels somewhat conservative to me, with many of the matchups looking like they’ve been seeded to pit lower-ranked teams against higher-ranked ones.

Currently if we get a game week with just three or four matchups of this caliber we celebrate it as a ‘big’ weekend[note]The biggest non-con weekend I can think of in recent memory was Week 1 of 2016: #20 USC vs. #1 Alabama, #3 Oklahoma vs. #15 Houston, #18 Georgia vs. #22 UNC, #11 Ole Miss vs. #4 Florida State, then also #10 Notre Dame vs. Texas, #2 Clemson vs. Auburn and #5 LSU vs. Wisconsin. That’s still about 50-60% less than the number of Top 25 matchups draw scheduling would produce in Week 4 (going by preseason rankings, anyway) [/note]. Thanks to the culture of avoidant-scheduling, any time two quality teams willingly schedule one another it’s headline news. We celebrate the morsels of quality games we are given instead of thinking up ways to make our choice of entertainment more entertaining.

And not only do the matchups above feel reminiscent of bowl season, they’d actually matter in the context of the season.

Save for a few T1 opponents inevitably flopping out of the gate each year, guaranteeing that every national title contender has an early ‘test’ completely redefines the texture and flow of the season. It would also hopefully quiet any ‘ain’t played nobody’ talk come CFP time—I’m not naive enough to think that won’t always exist to some degree, but to me the element of chance makes schedule discrepancies more admissible given how fanbases like to personify other schools’ scheduling practices.

Really, the biggest problem with this slate would be trying to pay attention to all of these games and finding quality TV space for all of them[note]And if If ADs/conferences feel that having all T1-T1 matchups on the same would be a detriment for their schools due to so much ‘attention competition’, maybe you could have half the T1s play against each other one week and the other half on another (this could apply to matchups for every tier).[/note]. I haven’t even mentioned the many intriguing T2 vs. T2 matchups that might be drawn on the same weekend (Northwestern-Iowa State, Memphis-FAU, and Iowa-Louisville in the case of my sample).

Best/Worst Case Scenarios

—

While the randomness of draws across the different tiers seems to balance things out even given the small sample size, I suppose over many simulations a statistical anomaly where a team draws the weakest or strongest (POPS-wise) opponent from each tier could occur.

For the former, this would look like a slate of Utah (28), USF (56), Rutgers (84), and UTEP (130), which would carry a POPS average of 74.5, still 19.06 stronger than the POPS average for FBS’ real 2018 schedules (see the ‘How Does It Compare’ sub-section).

The most difficult schedule a team could draw would consist of Alabama (1), Louisville (29), Arizona St. (57), and Navy (85) for an average of 43.00. While this would suck and is about doubly as difficult as the POPS average for the real 2018 non-con schedules, it’s still not as difficult as what Northern Illinois willingly scheduled for their 2018 non-con death march of Iowa (36), Utah (28), FSU (18), and BYU (76)—a POPS average of 39.50.

Again though, teams will naturally over and underperform which I suspect as a whole would only provide further balance to the system. Tier 4’s structure also prevents those schools from having to play a schedule that would set their program back several years.

Schedules Outside T1

—

Let’s look at some other schedules across the landscape. Of the teams in Tiers 1-3, T3’s Kansas St. (ranked #61) had the nation’s most difficult draw, with a POPS average 5 points lower than the next most difficult schedule:

[table id=32 /]

POPS Average: 45.25

Regardless of how home/away shakes out that’s pretty rough. Even though this is the anomaly of my draw rating-wise, I can see why ADs would be highly adverse to entering a system that could produce something like it[note]But it’s still not out of the realm of how non-conference schedules sometimes shake out currently. If you apply these tiers to the more difficult real 2018 out-of-conference schedules, Pitt is actually playing three T1 schools (Penn St., @Notre Dame, @UCF) and FCS Albany, as a cherry-picked example[/note].

But there’s also the possibility of ending up with a schedule like Georgia’s, the lowest POPS-rated schedule in my draw (see above). However, Georgia’s schedule was hardly an outlier as there were 40 schools with ratings between their 66.75 and 60, where the differences within appear negligible.

Three examples being:

[table id=26 /]

POPS Average: 66.00

[table id=27 /]

POPS Average: 63.75

[table id=28 /]

POPS Average: 64.75

Save for UCLA wanting to have anything to do with Texas A&M ever again, I don’t know if any AD would cry foul at these schedules (especially if they are on par to what everyone else is playing). They don’t deviate too much from the current norm yet still include enough strength in the form of a marquee opponent and 1-2 quality mid-tier teams that could serve as nice resume padding come December.

Tier 4 Schedules

—

Due to the mandatory scheduling of an FCS team and being double the size of the other tiers, T4 schedules need to be looked at in a vacuum. The tier also has a wider POPS disparity due to every team not having to play a T1 opponent.

When calculating POPS here, I gave FCS teams a rating of 192: there are 125 FCS teams of wildly varying quality so I just took the median number (125 / 2= 62.5) and added it to the number of FBS teams for an extremely rough placeholder ranking of 192. There’s likely a better way to do this and actually take individual teams into account (like Sagarin does), especially a since few FCS schools every year obviously outclass teams at the bottom of FBS. For now, I think it’s fine for simply communicating that T4 schedules are not comparable to T1-3’s.

Here are the softest[note]Discounting Charlotte, who because of math (and possibly my shortcomings with it) has to play two FCS teams[/note], median-est, and hardest schedules from the bottom tier:

[table id=29 /]

POPS Average: 118.5

[table id=30 /]

POPS Average: 98.00

[table id=31 /]

POPS Average: 85.00

UAB benefited massively by not drawing a T1 opponent and by getting the lowest-ranked team in T2. Most teams in T4 would probably view themselves in ‘rebuilding mode’ (with UAB, that and then some) and I imagine a schedule like this might be welcome as a way to build momentum and confidence via the W column, even if it means fans won’t see a David-Goliath encounter.

Kansas’ schedule is pretty on-par with their actual non-con schedule for the 2018 season (Nichols State, Central Michigan, Rutgers, Baylor). UL Lafayette ended with one easier than reality’s (Grambling, Miss St., Coastal Carolina, Alabama), but doesn’t everyone want to make a bowl?

How Does This Random Draw Compare With The Real 2018 Schedules?

—

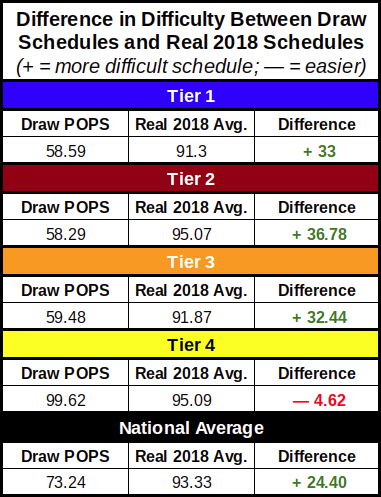

Of course, all this is meaningless without comparing the draw-produced schedules to what teams are actually scheduling. Using the same POPS calculation, I took each school’s actual 2018 non-conference slate (which ranges from 3-5 games) and calculated the same figure, then subtracted the draw-produced number from that to see the difference in difficulty between the two[note]Difficulty Difference = Actual POPS average for 2018 season — Projected draw POPS average[/note].

In the simulation, only two T1 teams were given schedules easier than their actual 2018 ones, and only three in T2 and two in T3. Over half (25) of the T4 teams ended up with an easier schedule, however many of these were by a very slim margin (10 ‘points’ or less).

For Tiers 1-3, the POPS average rose from 92.75 to 58.79. The biggest outlier in terms of getting a more difficult schedule was Oregon, who went from a three-game non-con slate in 2018 of BGSU (97), FCS Portland State (192), and SJSU (129) to a four-game one consisting of UL Monroe (107), BC (48), Minnesota (67), and Alabama (1). More difficult? Much, and maybe not the kind of slate on a first-year coach’s wish list, but more entertaining for fans and more helpful to a team with an outside title shot? Absolutely.

Going the other way, most of the T1-3 teams that ended up with easier schedules were from conferences with that play only three OoC games. The biggest benefactor in this group was UCLA, whose average opponent ranking decreased by just 18.75. In real-life 2018, the Bruins will play Cincinnati (88), Oklahoma (3), and Fresno St. (44), whereas my simulation handed them Minnesota (67), Texas A&M (24), Liberty (115), and Toledo (49). While A&M might not be Oklahoma, I think the overall difference is negligible.

For Tier 4, not having to face a team from every tier plus the mandatory scheduling of an FCS team (two in Charlotte’s case) produced schedules remarkably similar to their real-life 2018 ones. In fact, they would be just a touch easier by a degree of -4.62 according to POPS.

For the actual 2018 college football season, FBS teams[note]Except for the six Independent schools, who don’t have conference/non-conference seasons[/note] play a non-conference slate with a POPS average of 93.33. From most difficult to least, the range varies from 39.50 (Northern Illinois) to 139.33 (Oregon), nearly a 100-point difference in difficulty.

In my simulation, schedules for Tiers 1-3 (I left out T4 since their schedule makeup is slightly different) increased in difficulty to a 58.79 POPS average, nearly 35 points higher in difficulty than the real 2018 schedules. More importantly, the range in difficulty between teams was reduced to just 21.5 points, a 78% decrease!

Even with Tier 4’s mandatory scheduling of FCS teams, the POPS average was on-par (99.62) with the actual 2018 national average and the difficulty in difference was just 34.5[note]I discounted one outlier in this number—unless there is some workaround I am missing, one school has to play two FCS opponents which misrepresents this figure[/note].

Keeping in mind that home and away is not factored into any of this (and that in reality not all teams play four non-con games), I think these numbers and the schedules themselves are encouraging when given the ‘eye-test’: even to the more difficult set of draw-produced schedules, hardly any of them look ridiculously brutal.

So what’s the problem then with having (on paper) more egalitarian schedules and an exciting process to produce them?

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]uch of this piece is thinking out loud. My draw (which I basically did by hand) is a small sample size whose parity very well could be an outlier in a larger number of simulations.

There is probably no perfect solution as it pertains to non-con scheduling, and applying any ‘fix’ would undoubtedly create a slew of new ones. Below, I’ve tried to think of reasons draw scheduling wouldn’t work, then offer counterpoints and solutions where possible[note]If you’re reading this and have insight, particularly into the NCAA’s authority and what it would take for schools to all agree to the same scheduling practices, or as to how I could easily run a large number of simulations in an automated fashion, I’d be thrilled to hear from you.[/note]

Problem #1: Determining Home/Away (aka Who Is Paying Who?)

—

My biggest uncertainty (and possibly one of the biggest hangups for schools) is how exactly to determine home and away for each game. Home games provide a good chunk (if not all) of an athletic department’s budget and instilling a system that doesn’t mind that could be ruinous.

Is it mathematically possible to have every school play two home and two away dates[note]and could schools live off of that?[/note]? Could being in a certain tier determine how many home\away non-con dates you play (and could that bankrupt perennial T3-T4 schools)? What if home field advantage goes to whoever is ranked higher or willing to pay more to the other school, unless a neutral site location is agreed upon[note]If the price was right, lower-budget teams (well, their budgets) might not mind playing three of four non-con games on the road[/note]? Could an arbitrator or scheduling czar dictate both who is home/away and the amount of money being exchanged? What if X% of the home game revenue is paid to the away team?

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: The draw could be a biennial event which determines home and home non-conference series for the next two seasons (schedules would not be quite as balanced in that second year, however). Maybe conference schedules could be factored into the draw too so that a team is always averaging seven home games across a two-year span—six home games this year, eight next year, and repeat (h/t to Matt Grable for this idea).

At the same time, I wonder how often there could possibly be a scenario in which two teams’ resumes are so tight that one would trump the other solely by virtue of a marquee non-con road win over a home one.

It’s far beyond my wheelhouse, but I wonder too if a team’s distinct home-field edge could be factored into producing balanced non-con schedules.

Problem #2: Non-Conference Rivalries

—

The powers-that-be would probably hate changing to this system for innumerable reasons, but the biggest problem for fans might be the death of annual non-conference rivalries[note]Although said powers have never had a problem ending countless great rivalries in the name of conference realignment (see: Pitt-West Virginia, Texas-Texas A&M, Nebraska-most of the Big 12, countless others).[/note] like Florida-Florida State, Clemson-South Carolina, BYU-Utah, Georgia-Georgia Tech, Notre Dame-Everyone, and many others. Army-Navy would also need sorting out, the worst-case scenario being to play it as an exhibition game on its usual weekend (or simply make a 13-game exemption for the academies).

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: Reduce tier/pot-based scheduling to three games. For the fourth, allow schools to schedule rivals/whoever they want (which somewhat gets away from the whole creating more balanced non-con schedules thing) or to just receive a randomly assigned opponent that would keep their POPS average in an acceptable range.

But even with an at-will week or some sort of protected matchup system, many of these rivalries would likely still have to move from their signature weekends.

Problem #3: The Independents

—

What to do about the six (well, five[note]Notre Dame being the exception, like they are with everything. [/note]) independent schools is a big head-scratcher.

Even though ‘scheduling flexibility’ is a perk and reason for some of the Independents’ independence, it’s still a difficult task to fill a competitive schedule each year, especially once the conference slate begins for most other schools. Making all conference members play their non-con schedule at the beginning of the season might exacerbate the problem.

Keeping in mind what these teams’ actual 2018 schedules look like, the math to get to 12 via a draw system is rough:

- 4 games assigned through the draw (with a special no-FCS exception)

- 3 against other Independents

- 2 against FCS

- 3 against ???

Since these schools normally schedule two FCS opponents every year anyway, the draw exception is so that count doesn’t rise to three (only one of which can count toward bowl eligibility anyway).

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: I honestly have no idea. Join a conference, Indies. (Smart people, help me.)

Problem #4: Incentive and Status Anxiety

—

Because schools in T1-T3 all play one game against each other, there isn’t much incentive to try and climb up to the next one[note]Unless, as I mentioned before, home field is awarded to the higher-ranked team[/note] (other than if you have a preference on which weeks you play what kind of opponent). Even with a company (or multiple) sponsoring each Tier (as I did for fun in my example) and paying out some sum to each school therein, this might only further stratify the G5s and P5s.

Those programs stuck in their proud delusions/traditions from when they were strong a century ago might also hate the distinction of being labeled anything not ‘top tier’.

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: With wholesale changes to the college football TV landscape just a few years away, perhaps TV/digital rights deals could break up into being conference-based for the conference season and then Tier-based (T1 going to ABC/FOX/NBC/CBS; T2/T3 to ESPN networks; etc.) for the out-of-conference season. Conference networks might balk at not being able to show their conference members’ games, but there’s no reason those things couldn’t be ironed out.

You could also have the pots be secretive (determined by a ‘proprietary formula’) and do this whole process behind the scenes (no fun TV show though), although the format would probably make the tiers easy to reverse engineer.

Finally, perhaps a financial bonus could be issued to teams that elect to wear a tier-sponsor patch on their jersey during the non-conference season.

Problem #5: Recruiting

—

A small factor in modern scheduling is getting your school into areas/markets where there are large high school talent pools, creating visibility/awareness for your program in an area it might not have otherwise. The randomness of a draw system ends that (or would force teams to get more creative). Draw scheduling would also take the “In Year X you’ll get to play X” line out of recruiters’ talking points.

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: Recruiters have adapted to bigger changes in recent years. Maybe in some small way this could also create more parity in recruiting. I don’t know what that means exactly.

Problem #6: Draw Imbalance

—

I find the randomness exciting, but a team might not be thrilled about drawing all G5 teams, especially if their home game attendance is largely dependent upon opponent.

Some ADs and fans of national title contenders might also be unhappy about the prospect of having to face a fellow Top 10 school in week four while their rival plays one of the G5 teams that snuck into the top tier.

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: It’s beyond the scope of this write-up, but I think someone more mathematically inclined could devise a system where T1 teams were each guaranteed X amount of P5 and G5 opponents respectively, and so on with the other tiers.

You could also ‘protect’ the top 10 or so schools and keep them from playing one another, maybe splitting T1 into two halves that face each other in Week Four.

Problem 7: Upsetting the P5->G5->FCS Financial Ecosystem

—

I think it’s fine to reason that non-powers could get paid like they always have when drawn against most T1 and T2 opponents. But a problem might arise when they are drawn against a high-flying but lower budget school[note]FAU is a good example: the second-highest G5 school in 2018’s preseason S&P+ but 86th in athletic department revenue (in 2016)[/note] that can’t afford to pay them the same way a major program can.

If a G5’s athletic department relies heavily on the money they get from playing two or three non-conference paycheck games (as many do), a slate of Toledo, Troy, an FCS team, and Louisiana Tech could come with horrendous financial implications[note]Some points of reference for the kind of P5 to G5 money that would need to be made up for: Louisiana Lafayette pocketed $1.25 million by playing Texas A&M in 2017, Michigan paid $1 million to play App State in 2014, and Ohio State paid $850,000 to host Eastern Michigan in 2010.[/note].

An even bigger problem is if only T4s are playing FCS games, that halves the normal amount of FBS-FCS matchups (there were 98 in 2017; my beta plan creates only 47).

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: I think this is where a scheduling czar/arbitrator would have to come in and figure out how to negotiate (or dictate) the payouts for each of the three out-of-tier games so smaller schools can reach a ‘livable’ sum. Otherwise, separation between tiers will grow instead of meld.

A possible solution to keep money flowing to FCS schools would be to have T3s (like T4s) only play two of the three other tiers and also have a mandatory FCS game. That would however upset the balance of the other tiers’ schedules, possibly forcing them to play each other again some week.

Another solution could be to have FCS lottery balls a team in any tier could land until all 100 or whatever are drawn. But that too would defeat the whole point of trying to create balanced schedules and soon we’re back to where we started, but now with a big sideshow. And even with a guaranteed game, would there be a significant drop in money going to these FCS teams no longer playing against the biggest-name schools anymore?

If draw scheduling were to ever be put in place, it would certainly be the P5 schools holding the reins and getting first dibs on organizing (and reaping the benefits) of a ‘scheduling convention’. However, in a more fair world, maybe the host is not one school, but an entire conference. All of its member schools could split the revenue from tickets, sponsorship, and whoever is paying to broadcast the event. If duties rotated between the nine FBS conferences, this could give an occasional windfall to G5 schools[note]And in an even more fair world, only G5 schools would get to host and profit from the event[/note].

Problem #8: Transportation

—

An east coast team might balk at having to make multiple trips to the west coast (or vice versa) based on their draw. I am guessing team travel is something budgeted for at the beginning of each fiscal year, and scheduling games only a few months in advance could put a lot of guesswork into that process.

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: We live in a time when Hawaii and UMASS are scheduling home and homes (not to mention some conferences don’t seem particularly concerned with geography or travel logistics as it is). No real counterpoint here other than schools can figure it out.

Problem #9: Well-Supported Schools Staying Home For The Holidays

—

Since T4 teams have easier schedules (according to POPS), you might see a disproportionate amount of those schools qualifying for bowl games. Likewise, P5 schools in Tiers 1-3 eeking to 6 or 7 wins in a normal non-con schedule might fall short more frequently than before.

This might mean many unfulfilled bowl obligations from the major conferences each year and therefore lots of unenthused bowl invites to smaller schools without large alumni bases, or at least with ones unwilling to travel to El Paso, Mobile, or Boise in December.

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: It’s only speculation things would actually shake out this way—who knows if there would be much of a difference. However, the easier T4 schedules could mean more bowl game appearances for G5s which could in turn help make up for the funds lost by moving away from the contemporary paycheck game system (although schools would probably prefer the guaranteed, unshared money)[note]Although the four lowest-paying bowls (Frisco, Bahamas, Camelia, Arizona) only pay between $200k-$278k per team, the rest of the non-NY6 bowls begin paying at $802k (Cure Bowl) and the average payout of these games was $2,866,554 per team in the 2017 bowl season. These payouts go to a team’s conference and then are divvied out to its members.[/note].

Or, dare I say, we could always just add more bowls.

Problem #10: Enforcement

—

Who enforces all of this? What happens if a team refuses to play another? And how do you get basically every school to break the current cycle of 10-year-in-advance contract deals (which probably all have expensive buy-out/exit clauses associated with them)?

>>>SOLUTION/COUNTERPOINT: Give the NCAA something more useful to do? Not sure what kind of power they would have in mandating that schools take part in a system like this, although they do currently dictate and enforce several schedule-related bylaws (e.g., FBS teams must play 60% of their games against other FBS schools and play at least five home games) in their rulebook (bylaws 20.9.9.1 and 20.9.9.2).

Would adding more bylaws and telling schools they are postseason-ineligible unless they participate in the draw system be impossible?

—

Finally, one more potential issue we’ll never know the answer to by merely prognosticating: would it actually hurt G5 teams to play a non-con schedule on par strength-wise with what P5 teams are playing? Or for a G5 to have any shot of cracking a four-team CFP, does their schedule need to be head and shoulders above what P5s are playing? If the answers to those questions are respectively ‘yes’ and ‘no’, then the biggest question is would a draw system still be better for fans and for those tasked with scheduling than the current system where certain teams can dodge others?

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]cheduling will never be perfectly balanced in a sport with a 12-game regular season. No matter how they are determined, you can only play the schedule in front of you, then pray it looks good on paper in December.

But accepting there has never and will never be a level playing field in college football doesn’t mean we shouldn’t look for things we can tweak to give the sport a little more parity (and make it even more exciting).

There are obvious plot holes here—some small; others more glaring (such as the Independent issue). But despite its reputation, I believe college football is more open to change than we give it credit for: in the past five years we’ve seen a new post-season system installed essentially because enough people complained about the old one[note]After figuring out how to to preserve the current money/power structure, of course[/note] and we’re currently seeing a 100+-year old facet of the game slowly die before our eyes. Change in the sport isn’t impossible, it just requires the right impetus.

College football games and seasons are largely influenced by chance and chaos: pointy balls take funny bounces and headcase 18-to-22-year-olds often do headcasey things in big moments. This is a big reason why we watch. But trying to put together a playoff-worthy schedule 5-10 years in advance (which is basically throwing darts while standing on a merry-go-round, blindfolded), is the wrong kind of madness. Why not correct this problem by entrusting it to a system worthy of such a spectacle-laden sport, that still produces the kind of controlled chaos we love, and most importantly, is infinitely fairer.[note]Well, at least on paper[/note].

If you have answers, fiery critique, or ideas on how this idea could be built upon, I’d love to deep dive with you; leave a comment or send me an email[note]One thing I’d be really interested in doing is taking the final S&P+ rankings after the 2018 season ends and retroactively applying them to my simulated draw to see how POPS matched up to reality[/note].

—